« February 2007 | Main | April 2007 »

March 31, 2007

arXiv phase change

The arXiv has been discussing for some time the need to change the way it tags submissions. The principal motivation was that the number of monthly submissions in some subject classes (math and cond-mat, for instance) has been steadily rising over the past few years, and would have likely crossed the break-point of 1000 per month sometime later this year. 1000 is the magic number because the current arxiv tag is formatted as "subject-class/YYMMNNN".

The new tagging system, which goes into effect for all submissions tomorrow April 1st and later, moves to a "YYMM.NNNN" format and drops the subject classification prefix. I rather like this change, since, by decoupling the classification and the tag, it gives arXiv a lot more flexibility to adapt its internal subject classes to scientific trends. This will make it easier to place multi-disciplinary articles (like those I write, most of which end up on the physics arxiv), will (hopefully) make it less confusing for people to find articles, and will (potentially) let the arxiv expand into other scientific domains.

posted March 31, 2007 12:01 AM in Simply Academic | permalink | Comments (0)

March 30, 2007

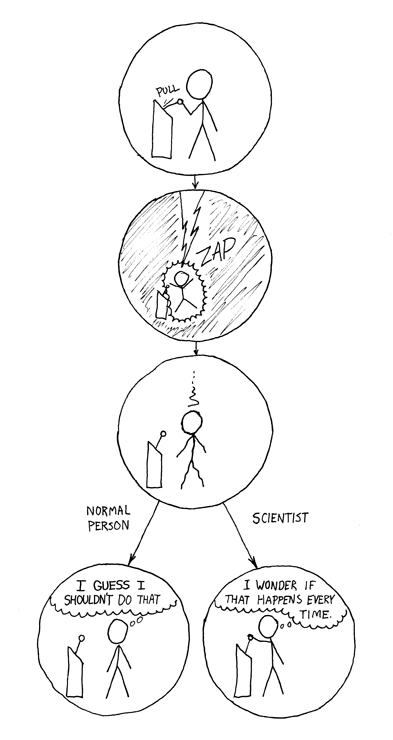

The difference

Via xkcd: "How could you choose avoiding a little pain over understanding a magic lightning machine?" So true. So true...

posted March 30, 2007 10:16 AM in Humor | permalink | Comments (3)

March 29, 2007

Nemesis or Archenemy

Via Julianne of Cosmic Variance, the rules of the game for choosing your archnemesis. The rules are so great, I reproduce them here, in full.

1. Your archnemesis cannot be your junior. Someone who is in a weaker position than you is not worthy of being your archnemesis. If you designate someone junior as your archnemesis, you’re abusing your power.

2. You cannot have more than one archnemesis. Most of us have had run-ins with scientific groups who range continuous war against all outsiders. They take a scorched earth policy to anyone who is not a member of their club. However, while these people are worthy candidates for being your archnemesis, they are not allowed to have that many archnemeses themselves. If you find that many, many people are your archnemeses, then you’re either (1) paranoid; (2) an asshole; or (3) in a subfield that is so poisonous that you should switch topics. If (1) or (2) is the case, tone it down and try to be a bit more gracious.

3. Your archnemesis has to be comparable to you in scientific ability. It is tempting to despise the one or two people in your field who seem to nab all the job offers, grants, and prizes. However, sometimes they do so because they are simply more effective scientists (i.e. more publications, more timely ideas, etc) or lucky (i.e. wound up discovering something unexpected but cool). If you choose one of these people as an archnemesis based on greater success alone, it comes off as sour grapes. Now, if they nabbed all the job offers, grants, and prizes because they stole people’s data, terrorized their juniors, and misrepresented their work, then they are ripe and juicy for picking as your archnemesis. They will make an even more satisfying archnemesis if their sins are not widely known, because you have the future hope of watching their fall from grace (not that this actually happens in most cases, but the possibility is delicious). Likewise, other scientists may be irritating because their work is consistently confusing and misguided. However, they too are not candidates for becoming your archnemesis. You need to take a benevolent view of their struggles, which are greater than your own. [Ed: Upon recovering my composure after reading this last line, I decided it is, indeed, extremely good advice.]

4. Archnemesisness is not necessarily reciprocal. Because of the rules of not picking fights with your juniors, you are not necessarily your archnemesis’s archnemesis. A senior person who has attempted to cut down a grad student or postdoc is worthy of being an archnemesis, but the junior people in that relationship are not worthy of being the archnemesis of the senior person. There’s also the issue that archnemeses are simply more evil than you, so while they’ll work hard to undermine you, you are sufficiently noble and good that you would not actively work to destroy them (though you would smirk if it were to happen).

Now, what does one do with an archnemesis? Nothing. The key to using your archnemesis effectively is to never, ever act as if they’re your archnemesis (except maybe over beers with a few close friends when you need to let off steam). You do not let yourself sink to their level, and take on petty fights. You do not waste time obsessing about them. Instead, you treat them with the same respect that you would any other colleague (though of course never letting them into a position where they could hurt you, like dealing with a cobra). You only should let your archnemesis serve as motivation to keep pursuing excellence (because nothing annoys a good archnemesis like other people’s success) and as a model of how not to act towards others. You’re allowed to take private pleasure in their struggles or downfall, but you must not ever gloat.

While I’m sure the above sounds so thrilling that you want to rush out and get yourself an archnemesis, if one has not been thrust upon you, count your blessings. May your good fortune continue throughout your career.

In the comment thread, bswift points to a 2004 Esquire magazine piece by Chuck Klosterman on the difference between your (arch)nemesis and your archenemy. Again, quoting liberally.

Now, I know that you’re probably asking yourself, How do I know the difference between my nemesis and my archenemy? Here is the short answer: You kind of like your nemesis, despite the fact that you despise him. If your nemesis invited you out for cocktails, you would accept the offer. If he died, you would attend his funeral and—privately—you might shed a tear over his passing. But you would never have drinks with your archenemy, unless you were attempting to spike his gin with hemlock. If you were to perish, your archenemy would dance on your grave, and then he’d burn down your house and molest your children. You hate your archenemy so much that you try to keep your hatred secret, because you don’t want your archenemy to have the satisfaction of being hated.

Naturally I wonder, Do I have an archnemesis, or an archenemy? Over the years, I've certainly had a few adversarial relationships, and many lively sparring matches, with people at least as junior as me, but they've never been driven by the same kind of deep-seated resentment, and general bad behavior, that these two categories seem to require. So, I count myself lucky that in the fictional story of my life, I've had only "benign" professional relationships - that is, the kind disqualified from nemesis status. However, on the (quantum mechanical) chance that my fictional life takes a dramatic turn, and a figure emerges to play the Mr. Burns to my Homer Simpson, the Newman to my Seinfeld, the Dr. Evil to my Austin Powers, I'll keep these rules (and that small dose of hemlock) handy.

Update, March 30, 2007: Over in the comment section, I posed the question of whether Feynman was Gell-Mann's archnemesis, as I suspected. Having recently read biographies of both men (here and here), it was hard to ignore the subtle (and not-so-subtle) digs that each man made at the other through these stories. A fellow commenter Elliot, who was at Caltech when Gell-Mann received his Nobel confirmed that Feynman was indeed Gell-Mann's archnemesis, not for scientific reasons, but for social ones. Looking back over the rules of the game, Feynman does indeed satisfy all the criteria. Cute.

posted March 29, 2007 12:04 AM in Simply Academic | permalink | Comments (0)

March 25, 2007

The kaleidoscope in our eyes

Long-time readers of this blog will remember that last summer I received a deluge of email from people taking the "reverse" colorblind test on my webpage. This happened because someone dugg the test, and a Dutch magazine featured it in their 'Net News' section. For those of you who haven't been wasting your time on this blog for quite that long, here's a brief history of the test:

In April of 2001, a close friend of mine, who is red-green colorblind, and I were discussing the differences in our subjective visual experiences. We realized that, in some situations, he could perceive subtle variations in luminosity that I could not. This got us thinking about whether we could design a "reverse" colorblindness test - one that he could pass because he is color blind, and one that I would fail because I am not. Our idea was that we could distract non-colorblind people with bright colors to keep them from noticing "hidden" information in subtle but systematic variations in luminosity.

Color blind is the name we give to people who are only dichromatic, rather than the trichromatic experience that 'normal' people have. This difference is most commonly caused by a genetic mutation that prevents the colorblind retina from producing more than two kinds of photosensitive pigment. As it turns out, most mammals are dichromatic, in roughly the same way that colorblind people are - that is, they have a short-wave pigment (around 400 nm) and a medium-wave pigment (around 500 nm), giving them one channel of color contrast. Humans, and some of our closest primate cousins, are unusual for being trichromatic. So, how did our ancestors shift from being di- to tri-chromatic? For many years, scientists have believed that the gene responsible for our sensitivity in the green part of the spectrum (530 nm) was accidentally duplicated and then diverged slightly, producing a second gene yielding sensitivity to slightly longer wavelengths (560 nm; this is the red-part of the spectrum. Amazingly, the red-pigment differs from the green by only three amino acids, which is somewhere between 3 and 6 mutations).

But, there's a problem with this theory. There's no reason a priori to expect that a mammal with dichromatic vision, who suddenly acquired sensitivity to a third kind of color, would be able to process this information to perceive that color as distinct from the other two. Rather, it might be the case that the animal just perceives this new range of color as being one of the existing color sensations, so, in the case of picking up a red-sensitive pigment, the animal might perceive reds as greens.

As it turns out, though, the mammalian retina and brain are extremely flexible, and in an experiment recently reported in Science, Jeremy Nathans, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins, and his colleagues show that a mouse (normally dichromatic, with one pigment being slightly sensitive to ultraviolet, and one being very close to our medium-wave, or green sensitivity) engineered to have the gene for human-style long-wave or red-color sensitivity can in fact perceive red as a distinct color from green. That is, the normally dichromatic retina and brain of the mouse have all the functionality necessary to behave in a trichromatic way. (The always-fascinating-to-read Carl Zimmer, and Nature News have their own takes on this story.)

So, given that a dichromatic retina and brain can perceive three colors if given a third pigment, and a trichromatic retina and brain fail gracefully if one pigment is removed, what is all that extra stuff (in particular, midget cells whose role is apparently to distinguish red and green) in the trichromatic retina and brain for? Presumably, enhanced dichromatic vision is not quite as good as natural trichromatic vision, and those extra neural circuits optimize something. Too bad these transgenic mice can't tell us about the new kaleidoscope in their eyes.

But, not all animals are dichromatic. Birds, reptiles and teleost fish are, in fact, tetrachromatic. Thus, after mammals branched off from these other species millions of years ago, they lost two of these pigments (or, opsins), perhaps during their nocturnal phase, where color vision is less functional. This variation suggests that, indeed, the reverse colorblind test is based on a reasonable hypothesis - trichromatic vision is not as sensitive to variation in luminosity as dichromatic vision is. But why might a deficient trichromatic system (retina + brain) would be more sensitive to luminal variation than a non-deficient one? Since a souped-up dichromatic system - the mouse experiment above - has most of the functionality of a true trichromatic system, perhaps it's not all that surprising that a deficient trichromatic system has most of the functionality of a true dichromatic system.

A general explanation for both phenomena would be that the learning algorithms of the brain and retina organize to extract the maximal amount of information from the light coming into the eye. If this happens to be from two kinds of color contrast, it optimizes toward taking more information from luminal variation. It seems like a small detail to show scientifically that a deficient trichromatic system is more sensitive to luminal variation than a true trichromatic system, but this would be an important step to understanding the learning algorithm that the brain uses to organize itself, developmentally, in response to visual stimulation. Is this information maximization principle the basis of how the brain is able to adapt to such different kinds of inputs?

G. H. Jacobs, G. A. Williams, H. Cahill and J. Nathans, "Emergence of Novel Color Vision in Mice Engineered to Express a Human Cone Photopigment", Science 315 1723 - 1725 (2007).

P. W. Lucas, et al, "Evolution and Function of Routine Trichromatic Vision in Primates", Evolution 57 (11), 2636 - 2643 (2003).

posted March 25, 2007 10:51 AM in Evolution | permalink | Comments (3)

March 21, 2007

Structuring science; or: quantifying navel-gazing and self-worth

Like most humans, scientists are prone to be fascinated by themselves, particularly in large groups, or when they need to brag to each other about their relative importance. I want to hit both topics, but let me start with the latter.

In many ways, the current academic publishing system aggravates some of the worst behavior scientists can exhibit (with respect to doing good science). For instance, the payoff for getting an article published in one of a few specific high-profile journals [1] is such that - dare I say it - weak-minded scientists may overlook questionable scientific practices, make overly optimistic interpretations the significance of their results, or otherwise mislead the reviewers about the quality of the science [2,3].

While my sympathies lie strongly with my academic friends who want to burn the whole academic publishing system to the ground in a fit of revolutionary vigor, I'm reluctant to actually do so. That is, I suppose that, at this point, I'm willing to make this faustian bargain for the time I save by getting a quick and dirty idea of a person's academic work by looking at the set of journals in which they're published [4]. If only I were a more virtuous person [5] - I would then read each paper thoroughly, at first ignoring the author list, in order to gauge its quality and significance, and, when it was outside of my field, I would recuse myself from the decision entirely or seek out a knowledgeable expert.

Which brings me to one of the main points of this post - impact factors - and how horrible they are [6]. Impact factors are supposed to give a rough measure of the scientific community's appraisal of the quality of a journal, and, by extension, the articles that appear in that journal. Basically, it's the the average number of citations received by an article (as tracked by the official arbiter of impact, ISI/Thompson), divided by the number of articles published in that journal, or something. So, obviously review journals have a huge impact because they publish only a few papers that are inevitably cited by everyone. The problem with this proxy for significance is that it assumes that all fields have similar citation patterns and that all fields are roughly the same size, neither of which is even remotely true. These assumptions explain why a middling paper in a medical journal seems to have a larger impact than a very good paper in, say, physics - the number of people publishing in medicine is about an order of magnitude greater than the number of physicists, and the number of references per paper is larger, too. When these bibliometrics are used in hiring and funding decisions, or even decisions about how to do, how to present, where to submit, and how hard to fight for your research, suddenly these quirks start driving the behavior of science itself, rather than the other way around.

Enter eigenfactor (from Carl Bergstrom's lab), a way of estimating journal impact that uses the same ideas that Google (or, more rightly, PageRank, or, even more rightly, A. A. Markov) uses to give accurate search results. The formulation of a journal's significance in terms of Markov chains is significantly better than impact factors, and is significantly more objective than the ranking we store in our heads. For instance, this method captures our intuitive notion about the significance of review articles - that is, they may garner many citations by defining the standard practices and results of an area, but they consequently cite very many articles to so, and thus their significance is moderated. But, this obsession with bibliometrics as a proxy for scientific quality is still dangerous, as some papers are highly cited because they are not good science! (tips to Cosma Shalizi, and to Suresh)

The other point I wanted to mention in this post is the idea of mapping the structure of science. Mapping networks is a topic I have a little experience with, and I feel comfortable saying that your mapping tools have a strong impact on the kind, and quality, of conclusions you make about that structure. But, if all we're interested in is making pretty pictures, have at it! Seed Magazine has a nice story about a map of science constructed from citation patterns of roughly 800,000 articles [7] (that's a small piece of it to the left; pretty). Unsurprisingly, you can see that certain fields dominate this landscape, and I'm sure that some of that dominance is due to the same problems with impact factors that I mentioned above, such as using absolute activity and other first-order measures of impact, rather than integrating over the entire structure. Of course, there's some usefulness in looking at even dumb measures, so long as you remember what they leave out. (tip to Slashdot)

The other point I wanted to mention in this post is the idea of mapping the structure of science. Mapping networks is a topic I have a little experience with, and I feel comfortable saying that your mapping tools have a strong impact on the kind, and quality, of conclusions you make about that structure. But, if all we're interested in is making pretty pictures, have at it! Seed Magazine has a nice story about a map of science constructed from citation patterns of roughly 800,000 articles [7] (that's a small piece of it to the left; pretty). Unsurprisingly, you can see that certain fields dominate this landscape, and I'm sure that some of that dominance is due to the same problems with impact factors that I mentioned above, such as using absolute activity and other first-order measures of impact, rather than integrating over the entire structure. Of course, there's some usefulness in looking at even dumb measures, so long as you remember what they leave out. (tip to Slashdot)

-----

[1] I suppose the best examples of this kind of venue are the so-called vanity journals like Nature and Science.

[2] The ideal, of course, is a very staid approach to research, in which the researcher never considers the twin dicta of tenure: publish-or-perish and get-grants-or-perish, or the social payoff (I'm specifically thinking of prestige and attention from the media) for certain kinds of results. Oh that life were so perfect, and science so insulated from the messiness of human vice! Instead, we get bouts of irrational exuberance like polywater and other forms of pathological science. Fortunately, there can be a scientific payoff for invalidating such high-profile claims, and this (eventual) self-correcting tendency is both one of the saving graces of scientific culture, and one of the things that distinguishes it from non-sciences.

[3] There have been a couple of high-profile cases of this kind of behavior in the scientific press over the past few years. The whole cloning fiasco over Hwang Woo-Suk's work is probably the best known of these (for instance, here).

[4] I suppose you could get a similar idea by looking at the institutions listed on the c.v., but this is probably even less accurate than the list of journals.

[5] To be fair, pre-print systems like arXiv are extremely useful (and novel) in that force us to be more virtuous about evaluating the quality of individual papers. Without the journal tag to (mis)lead, we're left having to evaluate papers by other criteria, such as the abstract, or - gasp! - the paper itself. (I imagine the author list is also frequently used.) I actually quite like this way of learning about papers, because I fully believe that our vague ranking of academic journals is so firmly ingrained in our brains, that it strongly biases our opinions of papers we read. "Oh, this appeared in Nature, it must be good!" Bollocks.

[6] The h-index, or Hirsch number is problematic for similar reasons. A less problematic version would be to integrate over the whole network of citations, rather than simply looking at first-order citation patterns. If we would only truly embrace the arbitrariness of these measures, we would all measure our worth by our Erdos numbers, or some other demigod-like being.

[7] The people who created the map are essentially giving away large versions of it to anyone willing to pay shipping and handling.

posted March 21, 2007 11:07 AM in Scientifically Speaking | permalink | Comments (0)

March 19, 2007

Things to read while the simulator runs; part 4

Having been awakened this morning at an ungodly hour by my allergies, and being incapable of coherent intellectual thought, I spent the quiet hours of the morning trawling for interesting stuff online. Here's a selection of the good bits. (Tip to 3quarksdaily for many of these.)

YouTube and Viacom are finishing their negotiation over Viacom's content's availability on YouTube in the courts. My sympathies certainly lay with YouTube's democratization of content creation and distribution. And, much as my democratic prejudices incline me to distrust monopolistic or imperial authorities, I agree that old media companies like Viacom should have a role in the future of content, since they're rather invested in the media whose creation they helped manage. Mostly, I think these old media empires are afraid that new technologies (like YouTube) will fundamentally change their (disgustingly successful) business model, by shifting the balance of power within the content business. And rightly so.

The physics of the very small still has a few tricks up its sleeve. Actually, I find the discovery of the D-meson state mixing (previously thought impossible on theoretical grounds) rather reassuring. There are clearly several things that are deeply confusing about our current understanding of the universe, and it's nice to be reminded that even boring old particle physics is a little more complicated than the ridiculously successful Standard Model gives it credit for.

(This one is a bit old, but still good, even 5 mouths out.) Last year, during the American leg of his book tour for The God Delusion, the indefatigable Richard Dawkins (whom I often write about, try here, here, here, and here) read a few excerpts to an audience at Randolph Macon Women's College in Lynchburg VA. Immediately afterward, he did an hour of Q&A with the audience, many of whom were from nearby Liberty University. Dawkins handled the frequently banal questions with both wit and aplomb.

Building on this theme, The New Atlantis has a nice article on the topic of the moral role that modern science plays in society.

On similar point, The American Scientist has a piece on the use and misuse of complex quantitative models in public policy, at least in terms of the environment. Being militantly critical of bad science in all forms, I wholeheartedly agree with the basic argument here - that good models must be predictive, accurate, interpretable, and live as close to the empirical evidence as is possible. Since models and theories are basically interchangeable formalisms, let me mangle one of Einstein's more popular quotations: Evidence without theory is lame, theory without evidence is blind.

posted March 19, 2007 08:56 AM in Things to Read | permalink | Comments (0)

March 12, 2007

Avian apprenticeships

Add to the list of amazingly human-like behaviors that various birds exhibit the act of apprenticeship. New research shows that unrelated manakins engage in cooperative courtship displays where the beta male doesn't get any action as a result, but learns the tricks of a good courtship display so that he can become a successful alpha somewhere else. So, in addition to the many other reasons why cooperation might emerge (many of which have game-theoretic explanations), we can now add training for future dominance. Fascinating. From DuVal's conclusions:

Lance-tailed manakin courtship displays are long and complex, and interactions with experienced males may be a critical component of learning display behavior. In accord with this hypothesis, beta males are generally younger than their alpha partners. Consistent performance of courtship displays with a successful alpha partner may allow betas to develop effect and appropriate displays that enhance their subsequent success as alphas. In systems such as this, in which factors other than kinship select for complicated cooperative behavior, long-term strategies to maximize future fitness may depend on social affiliations that reinforce the evolution of complex social structure.

E. H. DuVal, Adaptive Advantages of Cooperative Courtship for Subordinate Male Lance-Tailed Manakins. The American Naturalist 169, 423-432 (2007).

(Tip to Ars Technica.)

posted March 12, 2007 01:22 AM in Obsession with birds | permalink | Comments (0)

March 09, 2007

Art or fake?

M.V. Simkin, Scientific inquiry in modern art, E-print, (2007).

I report the results of the test, where the takers had to tell true masterpieces of abstract art from the fakes, produced by myself. Every picture can be described by the fraction of the test takers, who selected it as a masterpiece. When judged by this metric, the pictures show no stratification between masterpieces and fakes, suggesting that they are of about the same quality.

Simkin's website reverent.org hosts the quiz itself, which you can take. I scored a dismal 75% accuracy (better than chance, and slightly better than the average score of Ivy Leaguers and Oxbridge participants (71%), but shameful considering how much time I've spent in art museums over the years). His site has several other quizzes, too, and my self-esteem is mildly assuaged by the fact that, at least, I can distinguish human art from non-human crap (bird poop vs. Jackson Pollock: 100%, human vs. ape: 100%). I didn't dare to try to distinguish machine translation from Faukner.

posted March 9, 2007 10:54 AM in Humor | permalink | Comments (1)

March 08, 2007

Computer science vs. Computer programming

Suresh blogs about a favorite topic (and hobby horse) of mine: the image problem that Computer Science has over computer programming. Programming is really just a generalization of calculation, so to think that Computer Science is primarily about programming is like thinking Mathematics is primarily about punching numbers into an equation, or rearranging symbols on the page until you get a particular form. Of course, that's probably what most people in the world think math is about. It wasn't until college that I realized that Mathematics was more than calculation, or that Computer Science was more than just programming. Naturally, computer scientists are annoyed by this situation, and, if they were more inclined to self-ridicule, they might call it the CS vs CP problem: Computer Science vs. Computer Programming [1].

On a related point, recently, I've been interacting with a hard-working and talented high school student who isn't sure what she wants to study in college. Much to my delight, I frequently find myself connecting problems she's interested in with topics in theoretical Computer Science. For instance, just today, we talked about random numbers. She was amazed to learn that the P vs. NP question connects deeply with the question of whether strong pseudo-random number generators exist [2,3], and also that a sender and receiver can use a common pseudo-random number generator to make their conversation difficult to follow [4].

-----

[1] Sadly, the US Government also seems to think that CS = CP. When they say that demand for degrees in computer science is forecast to grow dramatically in the next 20 years, they don't mean that we'll need more algorithms people; they mean more IT people.

[2] The P vs NP question is one of the most important questions in all of mathematics, and the Clay Institute offers a cool $1 million for solving it, as one of its Millennium Questions. (My advisor likes to say that if you could show that P = NP, then you'd make a lot more than $1 million off the patents, and playing the stock market, among other things. The startling thing is that even this description underestimates this questions significance.)

[3] There are several great introductions to the P vs NP question, and many of them touch on the connection with random numbers. This one (starting on page 34, but see pages 37-38 in particular) is one that I just found via Google.

[4] Most scientists think of the pseudo-randomness of random number generators as either being a nuisance, or only being useful to replicate old results. Engineers - such a clever lot - use it to make many modern communication protocols more robust by hopping pseudo-randomly among a set of allowed frequencies.

posted March 8, 2007 08:37 PM in Computer Science | permalink | Comments (1)

March 07, 2007

Making virtual worlds grow up

On February 20th, SFI cosponsored a business network topical meeting on "Synthetic Environments and Enterprise", or "Collective Intelligence in Synthetic Environments" in Santa Clara. Although these are fancy names, the idea is pretty simple. Online virtual worlds are pretty complex environments now, and several have millions of users who spend an average of 20-25 hours of time per week exploring, building, or otherwise inhabiting these places. My long-time friend Nick Yee has made a career out of studying the strange psychological effects and social behaviors stimulated by these virtual environments. For many businesses, it is only just now dawning on them that games have something that could help enterprise, namely, that many games are fun, while much work is boring. This workshop was designed around exploring a single question: How can we use the interesting aspects of games to make work more interesting, engaging, productive, and otherwise less boring?

Leighton Read (who sits on SFI's board of trustees) was the general ringmaster for the day, and gave, I think, a persuasive pitch for how well-designed incentive structures can be used to produce useful stuff for businesses [1]. Thankfully, it seems that people interested in adapting game-like environments to other domains are realizing that military applications [2] are pretty limited. Some recent clever examples of games that produce something useful are the ESP game, in which you try to guess the text tags (a la flickr) that another player will give to a photo you both see; the Korean search giant Naver, in which you write answers to search queries and are scored on how much people like your result; and, Dance Dance Revolution, where you compete in virtual dance competitions by actually exercising. What these games have in common is that they break down the usual button-mashing paradigm by creating social or physical incentives for achievement.

One of the main themes of the workshop was exactly this kind of strategic incentive structuring [3], along with the dangling question of, How can we design useful incentive structures to facilitate hard work? In the context of games themselves (video or otherwise), this is a bit like asking, What makes a game interesting enough to spend time playing? A few possibilities are a escapism / being someone else / a compelling story line (a la movies and books), a competitive aspect (as in card games), beautiful imagery (3d worlds), reflex and precision training (shooters and jumpers), socialization (most MMOs), or outsmarting a computer (most games from the 80s and 90s when AI was simplistic), and even creating something unique / of value (like crafting for a virtual economy). MMOs have many of these aspects, and perhaps that's what makes them so widely appealing - that is, it's not that MMOs manage to get any one thing right about interesting incentive structures [5], but rather they have something for everyone.

Second Life (SL), a MMO in which all its content is user-created (or, increasingly, business-built), got a lot of lip-service at the workshop as being a panacea for enterprise and gaming [6]. I don't believe this hype for a moment; Second Life was designed to allow user-created objects, but not to be a platform for complex, large-scale, or high-bandwidth interactions. Yet, businesses (apparently) want to use SL as a way to interact with their clients and customers, a platform for teleconferencing, broadcasting, advertising, etc., and a virtual training ground for employees Sure, all of these things possible under the SL Life system, but none of them can work particularly well [7] because SL wasn't designed to be good at facilitating them. At this point, SL is just a fad, and in my mind, there are only two things that SL does better than other, more mature technologies (like instant messaging, webcams, email, voice-over-IP, etc.). The first is to make it possible for account executives to interact with their customers in a more impromptu fashion - when they log into the virtual world, they can get pounced on by needy customers that previously would have had to go through layers of bureaucracy to get immediate attention. Of course, this kind of accessibility will disappear when there are hundreds or thousands of potential pouncers. The second is that it allows businesses to bring together people with common passions in a place that they can interact over them [8].

Neither of these things is particularly novel. The Web was the original way to bring like-minded individuals together over user-created content, and the Web 2.0 phenomenon allows more people to do this, in a more meaningful way than I think Second Life ever will. What the virtual-world aspect gives to this kind of collective organization is a more intuitive feeling of identification with a place and a group. That is, it takes a small mental flip to think of a username and a series of text statements as being an intentional, thinking person, whereas our monkey brains find it easier to think of a polygonal avatar with arms and legs as being a person. In my mind, this is the only reason to prefer virtual-world mediated interactions over other forms of online interaction, and at this point, aside from entertainment and novelty, those other mediums are much more compelling than the virtual worlds.

-----

[1] There's apparently even an annual conference dedicated to exploring these connections.

[2] Probably the best known (and reviled) example of this is America's Army, which is a glorified recruiting tool for the United States Army, complete with all the subtle propoganda you'd expect from such a thing: the US is the good guys, only the bad guys do bad things like torture, and military force is always the best solution. Of course, non-government-sponsored games aren't typically much better.

[3] I worry, however, that the emphasis on social incentives will backfire on many of these enterprise-oriented endeavors. That is, I've invested a lot of time and energy in building and maintaining my local social network, and I'd be pretty upset if a business tried to co-opt those resources for marketing or other purposes [4].

[4] In poking around online, I discovered the blog EmergenceMarketing that focuses on precisely this kind of issue within the marketing community. I suspect that what's causing the pressure on the marketing community is not just increasing competition for people's limited attention (the information deluge, as I like to call it), but also the increasing ease by which people can organize and communicate on issues related to overtly selfish corporate practices; it's not pleasant to be treated like a rock from which money is to be squeezed.

[5] The fact that populations migrate from game to game (especially when a new one is released) suggests that most MMOs are far from perfect on many of these things, and that the novelty of a new system is enough to break the loyalty of many players to their investment in the old system.

[6] The hype around Second Life is huge enough to produce parodies, and to obscure some significant problems with the system's infrastructure, design, scalability, etc. For instance, see Daren Barefoot's commentary on the Second Life hype.

[7] The best example of this was the attempt to telecast Tom Malone's talk (complete with powerpower slides) from MIT into the Cisco Second Life amphitheater and the Cisco conference room I was sitting in. The sound was about 20 seconds delayed, the slides out of sync, and the talk generally reduced to a mechanical reading of prepared remarks, for both worlds. Why was this technology used instead of another, better adapted technology like a webcam? Multicast is a much better adapted technology for this kind of situation, and gets used for some extremely popular online events. In Second Life, the Cisco amphitheater could only host about a hundred or so users; multicast can reach tens of thousands.

[8] The example of this that I liked was Pontiac. Apparently, they first considered building a virtual version of their HQ in SL, but some brilliant person encouraged them instead to build a small showroom on a large SL island, and then let users create little pavilions nearby oriented around their passion for cars (not Pontiacs, just cars in general). The result is a large community of car enthusiasts who interact and hang out around the Pontiac compound. In a sense, this is just the kind of thing the Web has been facilitating for years, except that now there's a 3d component to the virtual community that many web sites have fostered. So, punchline: what gets businesses excited about SL is the thing that (eventually) got them excited about the Web; SL is the Web writ 3d, but without its inherent scalability, flexibility, decentralization, etc.

posted March 7, 2007 01:43 PM in Thinking Aloud | permalink | Comments (0)